Justice Select Committee - Courts and tribunal fees and charges inquiry

Thompsons Solicitors acts on behalf of most of the trade unions in the UK from offices in all four UK jurisdictions. At any one time we will, as a firm, be handling over 10,000 employment cases ranging from individual unfair dismissal matters and discrimination claims to multi party actions on, say, equal pay. We also offer a personal injury service to trade union members and run over 35,000 personal injury cases per year. We have a team of lawyers who act for members accused of work related crime.

We have previously given both oral and written evidence to both Select Committees and All Party Groups. Most recently we gave evidence to the Small Business, Enterprise & Employment Public Bill Committee in October 2014. We regularly respond to government consultations on matters within our professional expertise, and have responded to 12 in the last 12 months.

Executive summary

- Statistics show that the introduction of tribunal fees has deterred a very large number of potential claimants.

- The introduction of criminal court Charges has created an incentive for defendants to enter early guilty pleas in order to avoid incurring costs, thereby placing monetary concerns at the heart of the justice system.

- Civil court fees have increased by over 600% and access to justice has been impacted as a result.

- The current remissions regime does not adequately address the issue of affordability.

Introduction

The last government’s introduction of fees in tribunals and its regular hikes of civil court fees are having a detrimental effect on access to justice and are skewing the justice system in favour of the respondent/employer’s side, at the expense of the claimant.

The nature of employment and personal injury cases means they usually involve an individual claimant pursuing their claim against a large, well-resourced defendant. As the Supreme Court noted in 2010 “Employees as a class are in a more vulnerable position than employers. Protection of employees' rights has been the theme of legislation in this field for many years.”1 This inherent inequality has been greatly exacerbated by the policies of the last government who, by introducing fees, swung the balance even further in favour of employers. This is true even for claimants who are assisted in their claim by a union legal scheme.

The main focus of this submission is therefore upon that part of the inquiry which asks:

“How have the increased court fees and the introduction of employment tribunal fees affected access to justice? How have they affected the volume and quality of cases brought?”

Tribunal fees

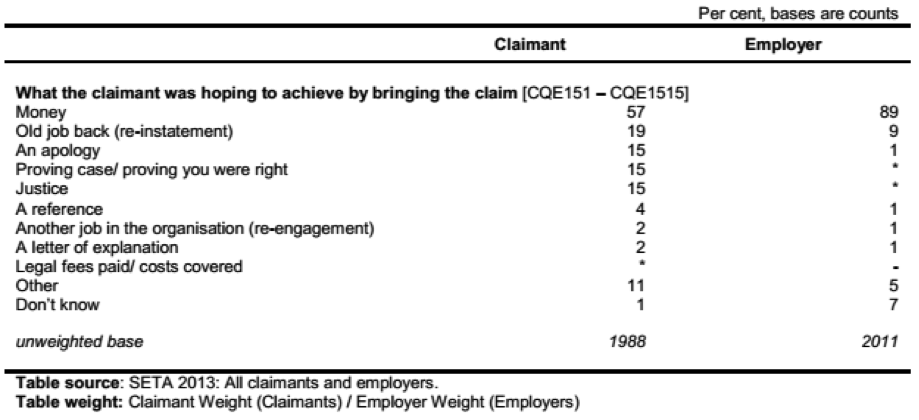

Although the remedies offered by the Employment Tribunal are almost exclusively monetary, and many claims are about unpaid money, research by SETA2 (table below) in 2013 showed that motivation amongst claimants is substantially about intangibles such as justice, securing an apology, and being told why they were treated in the way that they were.

The same research also asked whether fees would influence their decision to go to tribunal.3 49% responded that they would have been so influenced (rising to 69% in the 20-24 age group and 72% amongst part-time workers). 70% of unlawful deduction from wages claimants would have been influenced by fees.

In terms of numbers of claimants the Employment Tribunal has traditionally recorded figures for two types of case: single cases and multiples. Single cases are generally taken by tribunal users as the better measure of actual work being dealt with by the Employment Tribunal as they are a reflection of the number of cases which will have to be determined or dealt with individually. Multiple cases on the other hand contain many individuals but are administered using test or lead cases behind which the others stand or fall. Multiple claimants usually share the same representative and there are significant economies of scale which mean that the resource cost of 100 claimants in a multiple is nothing like that of 100 single cases.

In 2012-13 – the last year before fees – there were 54,704 single claims/cases, and 6,104 multiple claimant cases (involving a total 136,837 claimants), brought against a total 60,808 employers.

The ETS' annual reports regularly contain caveats about the capacity of certain multiples to skew the figures wildly, for example in the 2007/08 report 10,000 working time directive claims were issued several times each to comply with recurring limitation dates.

The government has a regrettable history of using the figures for multiple claims to justify its actions4 and the JSC is urged to be aware of this and to proceed with appropriate caution when looking at figures for case numbers.

When considering the position it is vital too to remember that there is a critical distinction between ‘claims’ and ‘cases’. A ‘claim’ is a breach of a particular right which an individual has suffered such as unfair dismissal, sex discrimination or unlawful deduction from wages. A ‘case’ is a grouping of all the claims an individual has, and will often contain several claims.5

When it introduced fees the government chose to ignore evidence of a long-term general downward decline in single claims lodged at the Employment Tribunal. In 2010-11 (i.e. the first financial year of the Coalition government) the number of ET cases fell by 13% from 78,700 to 68,500. This downward trend continued in both 2011-12 and 2012-13 so that when fees were introduced in July 2013 the level of claims was nearing its lowest since the turn of the century.

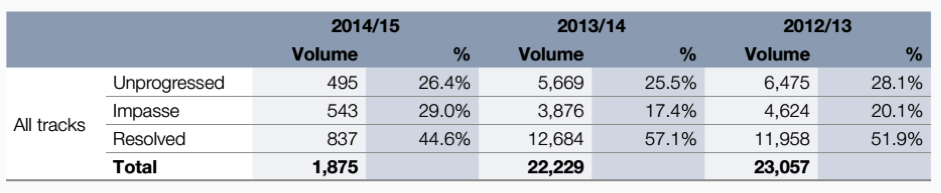

ACAS’ Pre-Claim Conciliation scheme (PCC) (the precursor to the current Early Conciliation scheme) was a voluntary scheme. ACAS published the following outcomes for its final 3 years of operation:6

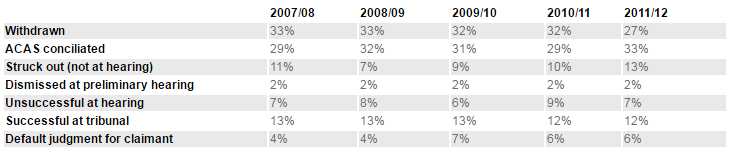

An analysis of the annual ETS reports yields the following outcomes information in which the consistency across the years is notable:

Given that it is routine practice in settlements for respondents to require claimants to withdraw their claims, equating the withdrawn totals entirely with unmeritorious or unsettled claims would be unfair. Similarly, ‘Struck out (not at hearing)’ and ‘default judgment’ generally relate to a failure to comply with a procedural requirement, and are not as a result of any assessment of merits. It is Thompsons’ experience that the cases which go to hearing do so on the whole either because they are the most difficult legally or factually, or because of the intransigence of one or more of the parties.

The introduction of tribunal fees in July 2013 saw the number of cases taken to the Tribunal fall dramatically. Fees are having a severe, negative impact on the ability of people, particularly those on low and average household incomes and more vulnerable members of society, to access the justice system.

It is important to remember that two government initiated changes to the tribunal system have operated together to reduce the figures; fees were introduced on 29 July 2013 and eight months later ACAS Early Conciliation on 6 April 2014. The government’s final impact assessment considered that when Early Conciliation and an increase in the continuous employment requirement for unfair dismissal claims (from 1-2 years), were combined the base number of claims would reduce to around 47,200 per year.7

It is important too to remember that the figures are distorted immediately either side of the introduction of fees as claimants and their representatives issued claims to avoid fees thereby bringing forward the issue of many claims, and possibly resulting in some claims being issued that otherwise would not have been.

The impact of fees - dramatic and stark

In July, when dismissing Unison’s appeal against the High Court’s rejection of its two applications for judicial review of the fees regime, Lord Justice Underhill stated:

“It is quite clear from the comparison between the number of claims brought in the ET before and after 29 July 2013 that the introduction of fees has had the effect of deterring a very large number of potential claimants.”8

The impact of fees was immediate and biting.

Table 1 in the Appendix shows the effect on the total of all claim types, and Table 2 breaks that down into individual claim types. Table 2 shows also how the impact has fallen more heavily on certain claims than others. For example,9 one of the least hit is age discrimination which reduced by ‘just’ 37%, and the next least affected was ‘Suffer a detriment / unfair dismissal – pregnancy’ which reduced by 45%. By contrast sex discrimination claims and working time directive cases were both down 90%, written pay statement cases by 80% and TUPE consultation by 78%. Across the whole list, claims were down 76%.10

This total level still appears slightly greater than anticipated by the government’s impact assessment. In 2014/15 129,966 claims were lodged which, using the methodology of the impact assessment, equates to 51,757 cases.

Despite being urged to identify qualitative rather than financial success criteria for their fees proposals, the government never did. It therefore avoided giving a measure by which to assess the true impact of the fees.

ACAS published a study of the efficacy of the Early Conciliation scheme: a scheme that is compulsory only in the sense that it must be triggered before an Employment Tribunal claim may be lodged, however, once triggered there is no obligation for a party to engage with it. ACAS’ research notes that 22% of those who triggered it ‘Just wanted to see if a settlement could be reached, and did not have a desire to submit an Employment Tribunal claim’,11 55% ‘Had to, in order to submit a tribunal claim, but was also keen to see if a settlement could be reached’ and 20% ‘Had to, in order to submit an Employment Tribunal claim’. The JSC should be very cautious in accepting any assertion that the number of cases handled by ACAS each relate to a claim that would otherwise have been issued at tribunal.

The same research also found that only 15% of cases settled, 22% went to the tribunal and 63% abandoned their claims altogether.12Compared to the Pre-Claim Conciliation results above this is startling since the old voluntary scheme led to 45% of cases settling, 29% reaching an impasse and 26.4% were not progressing. The research noted why:

“The single most frequently mentioned reason for not submitting an ET claim was that tribunal fees were off putting, reported by one quarter (26 per cent) of claimants (and their representatives) who had decided against claiming. Interestingly, responses did not vary by the income of the claimant or by the demographic profile of claimants; however, they did vary by membership of a trade union, with non-members being more likely to report that tribunal fees were off putting (30 per cent) compared with those who were members of a trade union or staff association (15 per cent).”13

“Claimants (and representatives) who reported that tribunal fees had been off putting were asked why this was. This question was asked in an open manner, but responses were attributed to a set of pre-existing answer codes and as such are not necessarily reflective of the language used Respondents could provide as many reasons as they wished and the most commonly mentioned reasons were:

- I could not afford the fee (68 per cent);

- The fee was more than I was prepared to pay (19 per cent);

- The value of the fee equalled the money I was owed (nine per cent);

- I disagree with the principle of having to pay the fee to lodge the claim (six per cent).

When asked what the main reason was six in ten (60 per cent) reported that they could not afford the fee, 15 per cent reported that the fee was more than they were prepared to pay and four per cent reported that they disagreed with the principle of paying the fee.”14

Although Thompsons supports Early Conciliation it seems clear that it has brought only a limited degree of access to justice for those who stay out of the Employment Tribunal system. The fact that fees were off-putting because they were either unaffordable, or poor value for money is very clear.

Remissions - not working

Given that affordability of fees is a central issue for this Inquiry, the effectiveness of remissions to address this is an important consideration.

While the government may point to fee remissions as the answer to concerns about access to justice, in reality they are little more than a fig leaf. For each separate fee incurred, a separate application for remission, with detailed evidence of income, must be provided. The guidance booklet itself is 31 pages long and the preparation of applications can take up to 30 minutes each, increasing the costs of the case every time a court fee is incurred. Such work also has an impact on the time of court and tribunal staff and represents an unnecessary bureaucracy as well as a backward step on the government’s stated march towards efficiency and cost-cutting.

In a speech to the EEF Vince Cable said:

“I want to make it very clear that for those with a genuine claim, fees will not be a barrier to justice. We will ensure that there is a remissions system for those who need help.”15

And in the House of Lords BIS minister Baroness Neville-Rolfe said:

“It is important to emphasise that the Government have been very careful to ensure that fee waivers are available for those people of limited means in order that they are not excluded from seeking redress through tribunals.”16

And in the final impact assessment on fees the government noted:

“…it is assumed that in future years 23.9% of claimants would routinely receive a full remission under Remissions 1 and 2; and it is assumed that a variable proportion of claimants would receive a full or partial remission under Remission 3, depending on the exact fee rate charged. Furthermore, it is assumed for simplicity that these distributions are independent of the fee-charging regime and that claimants in receipt of any type of remission would not alter their behaviour in response to fee-charging.”

The latest available information on remission comes from statistics issued by the Employment Tribunal.17 These show that in the period July 2013 up to June 2015 issue fees were paid in 44,405 cases with the full fee being paid in 68.2% of those cases. Remission was sought by 20,129 claimants and awarded in whole or part to 7,878. This means that 17.7% of issue fees requested were remitted which is clearly some way short of the impact assessment’s 23.9%.

The SETA research shows that getting paid what they are owed and a feeling that justice was done are the key drivers for potential claimants at the Employment Tribunal. Despite this 41% of those who approached ACAS through Early Conciliation abandon their quest for justice there18, with just 15% settling, down from the 45% - 57% range in the final years of the pre-claim conciliation scheme. The SETA and ACAS research papers both show the deterrent effect of fees as the single biggest factor in the decision not to go ahead and the remission statistics show that it is not assisting the numbers anticipated.

The government’s response to the dramatic fall in numbers is to point to the availability of remissions, but a more candid and we believe more accurate reaction was given by the then Enterprise Minister (now Minister for the Cabinet Office and Paymaster General) Matthew Hancock who claimed in a speech in March 2014 that the ‘success’ of the policy had been proven and that the fees would stop businesses being “ruthlessly exploited” by workers “trying to cash in”.

The Redundancy Fund - claimants being forced to pay fees out of their redundancy pay

In the event of an employer becoming insolvent and being unable to pay redundancy payments, an effected employee can make a claim to the Redundancy Payments Office (RPO). Sometimes they are paid just on application but others require Employment Tribunal proceedings to be issued. Redundancy pay claims are type A cases and so attract an issue fee of £250 and a hearing fee of £150.

Incredibly the RPO refuses to reimburse the fees which can mean an individual’s payment being reduced by up to £400. The worker, having lost their job, has the limited capped amount available from the government via the RPO reduced by a government imposed fee, forcing them to pay to recover what is lawfully theirs. This demand for payment of the tribunal fee from people when they are most financially vulnerable places the government in breach of international obligations.

Directive 2008/94/EC provides:

“It is necessary to provide for the protection of employees in the event of the insolvency of their employer and to ensure a minimum degree of protection, in particular in order to guarantee payment of their outstanding claims, while taking account of the need for balanced economic and social development in the Community. To this end, the Member States should establish a body which guarantees payment of the outstanding claims of the employees concerned."

Article 3 provides:

"Member States shall take the measures necessary to ensure that guarantee institutions guarantee, subject to Article 4, payment of employees' outstanding claims resulting from contracts of employment or employment relationships, including, where provided for by national law, severance pay on termination of employment relationships."

Civil court fees

An effective, transparent justice system that works for all people equally should be at the heart of an advanced democracy. Fees to raise funds to cover cuts in central budgets means accountability suffers and makes the courts increasingly only accessible to the wealthy.

The government has indicated that over 90% of money claim litigation is for less than £10,00019 and the majority of those will be at the lower end of that range. The enhanced fees represent a significant percentage of that sum.

Many claims are settled but need to be concluded by a consent order. A case settling for £1,500 will have had an issue fee of £115 and now requires a further £100 for the final consent order. A consent order fee which is nearly 10% of the settled value of the claim is not, as the government has sought to argue, ‘low compared to the overall costs of litigation’.

If there had been just one application within the £1,500 case then the total fees would be £475 (£115 plus £255 plus £100), almost one third of the settlement value.

In our experience, many applications are necessary to force the other party to comply with a Rule or Direction and a high proportion of those applications are ultimately agreed between the parties and a consent order lodged. Many courts demand separate fees for both the initial application and the consent order, which means that, for a simple application, the court fees could be in the region of £380. In our experience the higher the costs of an application the more likely respondents are to defend it.

Claimants are not protected by Qualified One-Way Shift Costing (QOSC) provisions in respect of pre-action applications and the default position is that the party making the application bears the costs.

Increasing the fees for general applications means that it increasingly makes more economic sense to enter litigation with full proceedings rather than make a pre-action application, particularly in lower value claims where the application fees will outweigh the issue fees.

The last time the government consulted on ‘enhanced court fees’ (a six week consultation ending 27 February 2015), the majority of consultees disagreed with the proposals, which included fee increases of over 600%. Yet still the government went ahead. We are concerned that the government’s cost-cutting and revenue-raising zeal is blinding them to the range and number of expert voices expressing concern with its fees regime in the courts and the Tribunal.

Criminal court charges - implemented without proper consultation

The charges have been set at a high level and crucially are not means tested, they act as yet another post-May 2010 barrier to individuals being able to assert their rights and gain access to justice.

Facing fees of £520 - £1,200, should they be found guilty, as opposed to a much smaller sum if they enter an earlier guilty plea creates a perverse incentive. We fear individuals who are under significant pressure, including financial pressure from high contributions to fund their legal aid, may in some instances decide to enter an early guilty plea. Individuals worried about the financial impact of defending their innocence may decide not to contest a case simply to safeguard their family and home.

The only discretion available to the court in respect of the Charge is over how the payment is ultimately made – i.e., by instalments etc, making it an extremely blunt instrument. The lack of flexibility as to the level of the charge is surprising given that Magistrates and Crown Court Judges are in an ideal place, having heard the case, to decide what is appropriate, based on, inter alia, the severity of the offence, the particular circumstances, the individual’s ability to pay, as well as the impact imposing such a Charge would have on the individual and their family.

The lack of flexibility means the Charge has a disproportionate effect on benefit claimants or those on a low income, criminalising individuals who feel a financial imperative to plead guilty.

We have seen no evidence regarding the costs of collecting/enforcing the Charge and we are not aware of any study being undertaken. The reality may well be that any income derived from making the Charge will be substantially diminished by court staff time administering and policing the system.

Not only is there no attempt to look at administration costs but there is no means by which to show (if there is any income from the Charge) that it is being used to directly benefit the criminal courts system/those individuals within that system. There should be proper transparency around the cost of gathering the charge and its use.

Thompsons would be happy to contribute further to this Inquiry by providing oral evidence.

For further information:

Stephen Cavalier, Chief Executive of Thompsons Solicitors

Congress House

Great Russell Street

London

WC1B 3LW

StephenCavalier@thompsons.law.co.uk

1Gisda Cyf v Barratt [2010] IRLR 1073, Supreme Court, per Lord Kerr at paragraph 35

2Table 5.6, Findings From the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications 2013, BIS Research Series No.177, June 2014.

3Supra footnote 2, page 38ff

4Not least in the impact assessment which sought to justify fees in the first place, paragraphs 1.9ff

5Statistics from the ETS regularly show an average of between 1.8 and 2.2 claims per case

6ACAS Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15, page 37

7Paragraphs 3.13 and 4.10, Impact Assessment TS 007, 30 May 2012

8Unison, R (On the Application Of) v The Lord Chancellor [2015] EWCA Civ 935 at paragraph 67

9Comparison of Q1 figures for 2013/14 and 2014/15

1038% of the total is assumed to be single claims. The balance of 62% is assumed to be multiples with an average of 34 members. The single claim total it added to one thirty-fourth of the multiple total

11ACAS Research Paper, Evaluation of Early Conciliation (Reference 04/15) Matthew Downer, Carrie Harding, Shadi Ghezelayagh, Emily Fu and Marina Gkiza (TNS BMRB), page 33

12Supra, page 64

13Page 97

14Page 98

15https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/reforming-employment-relations,23 November 2011

16http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201415/ldhansrd/text/150126-gc0001.htm#1501269000145 26 January 2015

17Statistics on Employment Tribunal Fees (JADU) data, 29 July 2013 to 30 June 2015, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/459585/annex-d-tribunal-fees.xls

1841% is the 63% figure less the 22% who say they wouldn’t have been a claimant in any event

19https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/proposals-for-further-reforms-to-court-fees/supporting_documents/cm8971enhancefeesresponse.pdf